Although we live in a society that believes in equality between men and women and encourages female participation in active life, the truth is that the role of women is still not played in total equality with men in many sectors.

The legal area is no exception, although the number of women practicing today is much higher than in the previous century.

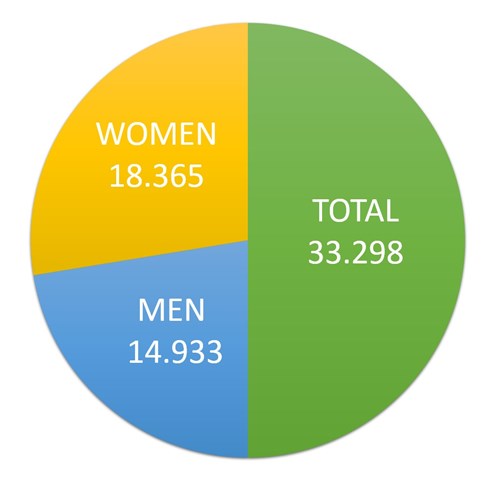

A study by PORDATA, whose last update dates from 06 November 2020, indicates that in Portugal in 2019 there were 18 365 women law graduates registered at the Bar Association and "only" 14 933 men.

Lawyers: total and by gender. Data Sources: DGPJ/M. Source: PORDATA

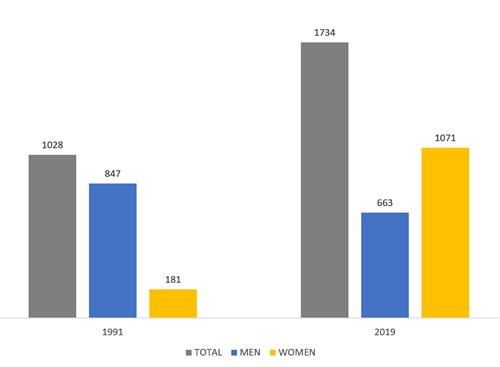

If we think in terms of judicial magistrates, the same study indicates that of the total of 1,734 judges in the courts of first instance and higher courts, 1,071 are women. Curiously, this numerical increase only occurred in 2007 (846 women and 833 men), since in 1991 the difference was still abysmal: 847 male judges and only 181 female judges.

Judicial magistrates: total and by gender. Data Sources: DGPJ/M. Source: PORDATA

This data may lead us to believe that, after all, the judicial world is quite full of women and that the term "inequality" does not make sense. However, what is at stake here is effectively a question of parity in relation to the balance between personal and professional life, career progression, earned income and access to top positions.

In 2017, the gender quota law came into force in Portugal with the aim of achieving a greater balance of opportunities between genders.

However, and despite the exponential growth in the number of women in the legal profession, it is representative that this growth has not been accompanied by an equal increase in their participation in the executive or disciplinary management bodies of the Bar Association, namely in its presidency positions: since 1927, the Bar Association has only had two women President. In 1990, Maria de Jesus Serra Lopes was elected President of the Bar Association for the three-year period 1990-1992, the first female lawyer to hold this position. On 29 November 2013, Dr. Elina Fraga was elected President of the Bar for the 2014-2016 term.

Throughout Europe, the inclusion of women in the legal profession only occurred at the end of the 19th century / beginning of the 20th century.

In Portugal, Dr. Regina Quintanilha was the first woman to have a degree in Law and to be a Lawyer, as well as the first female prosecutor, the first female notary and the first female land registry agent.

Regina Quintanilha

As a female lawyer she made her debut at the Boa Hora Court, on 14 November 1913, after the Supreme Court of Justice had given her authorization to practice law. Nevertheless, it was only in 1918 that Decree no. 4676, of 19 July, consecrated the full opening of the Legal Profession to women.

Born in Bragança, Regina da Glória Pinto de Magalhães Quintanilha de Sousa Vasconcelos, joined the Faculty of Law at the University of Coimbra in 1910, "forcing" the University Council to meet on purpose to deliberate on the entry of a female student. On the day she entered the University, on October 24th 1910, aged only 17, Regina Quintanilha was welcomed by the whole Academy formed in rows with the capes on the floor giving her passage.

She finished her degree in three years and in 1913, at the age of 20, she was invited to be the principal of the recently created Coimbra Female High School. She refused, because she wanted to pursue a career that the Portuguese Civil Code of 1867 prohibited women to pursue, which was the practice of law.

In Portugal, she was once again the first woman to exercise the functions of Registrar of the Land Registry and Notary Public.

It is important to mention that in the last years of the Monarchy and in the years of the First Republic it was not common to have ladies studying in Coimbra, even in the higher classes, and practising a liberal profession. Only in 1890 girls are allowed to attend public lyceums and only 16 years later the first female lyceum is created. In 1910, compulsory schooling was from age 7 to 11. For women, an elementary education was normally assigned, and they were not asked to do more than the functions of wife and mother.

The mindsets of Portuguese society at the time were not prepared to give women a place in the liberal professions.

In the UK, meanwhile, the first woman to obtain a law degree was Eliza Orme, who graduated from University College London in 1888.

She was not allowed to practise as a Lawyer. But it was in 1919, with the passing of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, that women were allowed to enter the legal profession. This had been challenged in 1914 in a case, Bebb v Law Society, in which the Court of Appeal held that women did not fall within the legal definition of "persons" and therefore could not become lawyers. The 1919 Act also allowed women to serve on juries for the first time.

She was not allowed to qualify to practice as either a solicitor or a barrister. It was not until 1919, with the passage of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 that women could enter the legal profession. This had been challenged in 1914 in a case, Bebb v Law Society, in which the Court of Appeal found that women did not fall within the legal definition of "persons" and so could not become lawyers. The 1919 act also allowed women to serve on juries for the first time.

Eliza Orme

In Germany, the actress, writer and activist Anita Augsburg was the first woman to obtain a law degree in Germany (1897) but it was not until the law was changed in 1922 that she was allowed to practice law.

Her commitment to women's rights led her to decide, after several years of successful work, to study for a law degree. She went to the University of Zurich, Switzerland, because women in Germany still did not have equal access to universities. Alongside Rosa Luxemburg, with whom she had a turbulent relationship, she was one of the founders of the International Association of Women Students (Internationaler Studentinnenverein). She completed her studies with a doctorate in 1897, the first doctorate in law in the German Empire. However, she could not practice as a lawyer, as women were not yet allowed to do so.

Anita Augsburg and Fraulein Heyman, Vice-Pres. of the Women's Internat'l League, snapped at the Woman's party headqrts, in Wash.

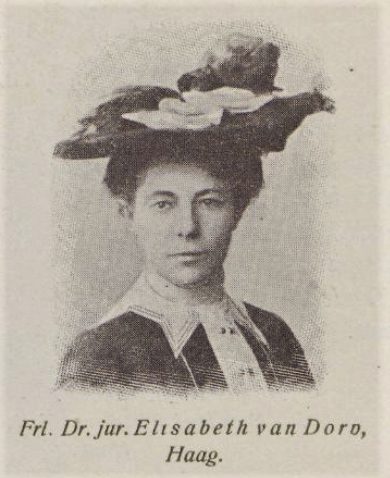

In the Netherlands, Elisabeth Carolina "Lizzy" van Dorp distinguished herself as a lawyer, economist, politician and feminist.

Van Dorp studied law at Leiden University, becoming the first woman in the Netherlands to obtain a law degree in 1901, and to be promoted in 1903. She then practised private law, and became active in various feminist movements, although she opposed the more radical forms of feminism—her focus was on instituting female suffrage.

Elisabeth Carolina van Dorp

Another example, this time in Switzerland, was Emilie Kempin-Spyri,the first woman in Switzerland to graduate in law and be accepted as an academic professor.

However, as a woman, she was not allowed to practice as a lawyer; she therefore emigrated to New York, where she taught at a law school she established for women. Emilie Kempin-Spyri was the niece of Johanna Spyri, a Swiss author of novels, notably children's tales, best known for her book Heidi.

Emilie Kempin-Spyri

A century later and despite the evolution of the role of women in the legal profession, it still happens all too often that women are passed over when they seek to increase power or influence. In other words, when they want to assume the role of leader.

The fact is that the legal profession has a long way to go before it provides its members with the equality and justice it so zealously seeks for its clients. Empirical evidence clearly demonstrates that gender bias still exists, and that they are a barrier to success. And this is the time to transform the legal profession.

Over the past decade, the (by invitation only) Women’s Power Summit on Law and Leadershi event has been inviting the "Who's Who" of influential women in the legal profession to generate ideas and lead change and they have left a number of recommendations on what one can do to each be a driver of this change:

- Selecting a woman to be part of an (important) client team;

- Sharing authorship credit with a woman.

- Hire a woman as an outside advisor or select a woman to be responsible for a client relationship.

- Disclose a woman's accomplishments to a leader within and/or outside your organization.

- Refer a business and/or job opportunity to a woman.

- Recommend a woman to be a speaker at a conference or event.

- Engage in peer-to-peer mentoring....

- Etc.